From DEI to Cultural Design

A new framework for meaningful, inclusive culture-building.

It has become increasingly clear that, at scale, Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) initiatives as we know them have often struggled to achieve their intended outcomes. While the backlash from some political quarters has played a role in undermining public confidence, the issues run deeper than political tides or cultural fatigue.

Despite decades of effort, recent data shows that a significant portion of the U.S. population—particularly white Americans—now perceives reverse discrimination as a greater problem than systemic racism. This perception, however misaligned with the data, points to a cultural polarization that DEI has not resolved—and may, in some cases, have inadvertently amplified.

Academic research is beginning to underscore these limitations. Many DEI programs have not demonstrated sustained positive impact, and in some cases, have even correlated with increased workplace bias. Clearly, while the goals of DEI remain vital, the strategies require reevaluation.

An Elephant in Every Room

The persistence of inequity, conformity, and exclusion in organizations demands ongoing attention. The dissolution of certain DEI programs does not mean the underlying issues have been solved. Instead, they continue to surface—subtly and not-so-subtly—in every workplace, every boardroom, every team dynamic.

There is still an elephant in every room. And there is a price to pay for ignoring this fact.

What’s needed now is not a retreat into silence or avoidance, but a new framework for meaningful, inclusive culture-building. One that acknowledges past efforts without being bound by their limitations. One that invites fresh energy and broader participation.

Understanding where DEI Went Wrong

To build more effective approaches, it’s essential to understand why many DEI programs have struggled. Four interrelated issues often emerge:

Overly narrow categories: DEI efforts often focus on a limited set of identity categories—typically race, gender, and a few others—while neglecting many lived experiences of marginalization or exclusion. This can alienate individuals who don’t see their challenges reflected or acknowledged.

Rigid identity frameworks: By centering fixed identity categories, DEI programs can unintentionally reinforce stereotypes or encourage reductive thinking. In emphasizing difference, they may undercut the recognition of shared complexity.

Excessive burden on organizations: While systemic injustice is a legitimate societal concern, placing the weight of redress on individual workplaces—often without adequate support or clarity—can overwhelm teams and diminish efficacy.

A deficit-based tone: Many DEI efforts focus on diagnosing problems and identifying faults. While necessary, this emphasis can lead to defensiveness, compliance-based behavior, and a culture of blame, rather than open engagement.

A New Approach: Cultural Design

To move forward, we propose an evolution: from DEI to Cultural Design. This is not about abandoning the values of fairness, inclusion, and equity—but about pursuing them through a more adaptive, creative, and locally grounded methodology. Cultural Design prioritizes co-creation, listening, and experimentation over compliance and correction.

Here’s how Cultural Design responds to DEI’s key challenges:

Starts with listening: Rather than assuming which categories are most relevant, Cultural Design begins with deep, qualitative exploration to identify the real tensions, patterns, and unmet needs within a given workplace. It is grounded in context, not preconception.

Embraces identity ecologies: Cultural Design acknowledges that people carry multiple, intersecting identities. By de-emphasizing fixed labels and instead inviting whole-person engagement, it helps reduce stereotyping and supports more authentic connection.

Focuses on local agency: Instead of asking local organizations to solve global injustices, Cultural Design empowers teams to improve the specific cultures they inhabit. This makes the work feel more actionable, meaningful, and sustainable.

Builds on what’s working: Cultural Design emphasizes generative change—what can be created, not just what must be dismantled. It promotes psychological safety by encouraging curiosity, creativity, and even humor, helping participants feel more ownership over cultural evolution.

From this perspective, culture is not a static structure to deconstruct—it is a living system to be shaped. When organizations move from correction to co-creation, they tap into deeper motivation and broader engagement.

Cultural Design is not a repudiation of DEI, but a next step. It is an invitation to organizations that value inclusion but seek a framework better suited to today’s complex and fast-changing social landscape. By focusing on lived realities, shared aspirations, and local agency, Cultural Design helps teams not only address bias but build cultures of belonging and vitality.

Because ultimately, the goal is not to fix people—it’s to design environments where people can thrive, together.

This essay is from VIBE LABS: Resources for Resonance

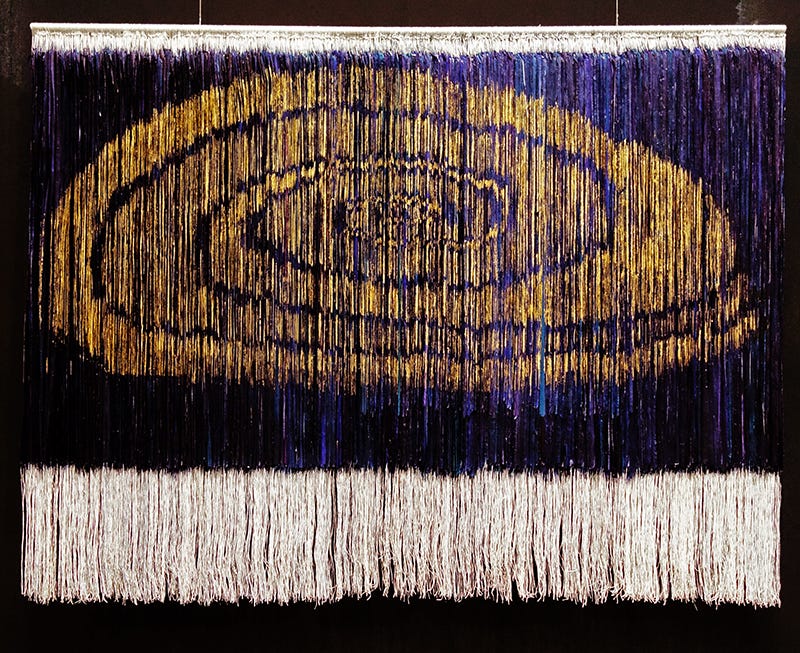

We take on elephants – there’s one in every room

We are:

Robert Kelley Ayala, strategy consultant, executive coach, and writer with a background in technology, venture capital, and organizational design. He holds a B.S. from Duke University, an MBA from HEC-Paris and an M.S. in organizational psychology from Birkbeck College, University of London.

Daniel P. Görtz, Ph.D. in sociology at Lund University, Sweden. Daniel’s doctoral thesis was a close study of on-the-ground police work, decoding racial and ethnic biases and practices in the highly multicultural city of Malmö. He is the co-author of several books on the cultural sociology of “metamodernism”, including The Listening Society.